Why my solidarity with Palestinians facing genocide today is part of my Jewish heritage.

Saira Weiner was interviewed by Anne Alexander

“The movement which has developed in solidarity with Palestine has been really transformative. The amazing thing is that there are hundreds and hundreds, sometimes thousands of young people involved. In Liverpool I would say that they are predominantly Muslims, but this movement is also bringing together people from very disparate backgrounds who are making common cause over their rage and horror at the genocide, war and ethnic cleansing in Palestine.

We have had some large local protests, for example when Jeremy Corbyn spoke at a demonstration of 3-4000 people. Liverpool isn’t a massive city, despite its huge reputation, so this has a real impact.

The movement is very vibrant. Walk around town with a Palestine badge or a keffiyeh, you’ll experience no hostility or abuse but just people nodding in support. We’ve seen poorly paid restaurant workers and shop workers applauding the demonstrations on the main streets.

This has changed the atmosphere in the city centre in other ways. We often get religious bigots with pictures of abortions and they have been noticeably less prominent in recent months. Liverpool has a huge history of industrial fightback, but it feels now more like a place for everyone. There are regular vigils for Palestinian medical workers. Even when there is no formal demonstration called, people show up, even without much political leadership.

What has been less effective has been the organised trade union movement getting those people onto coaches for the national demonstrations or into meetings.

I have been trying to organise at work at Liverpool John Moores University (LJMU). Immediately after 7 October it was very difficult. People were victimised, racialised Muslims in particular. We found out that the University had implemented the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance definition of anti-semitism without telling us. I was deeply concerned that this would be used to victimise people who spoke out in solidarity with Palestine.

I organised a meeting with the Vice Chancellor who confirmed that LJMU had adopted the IHRA definition and not the additional controversial examples which conflate anti-semitism and anti-Zionism. He confirmed that the University supported freedom of speech. However, the University wouldn’t say this in public, so our branch immediately put out a public statement about what had been discussed in the meeting.

It was vital that we acted quickly because we knew that members and students were under pressure for speaking out over Palestine. For example, a Muslim woman student from Yemen was called with a meeting with the head of HR to be told that she wasn’t allowed to use the word “genocide” in tweets. This led to an atmosphere of fear on campus. A member of staff, who is quite well known for his work opposing the government’s racist Prevent duty, had a complaint made against him by the Department for Education. A formal investigation took place but found nothing.

This is why taking the enthusiasm and anger from the streets into our workplaces is crucial to give people confidence.

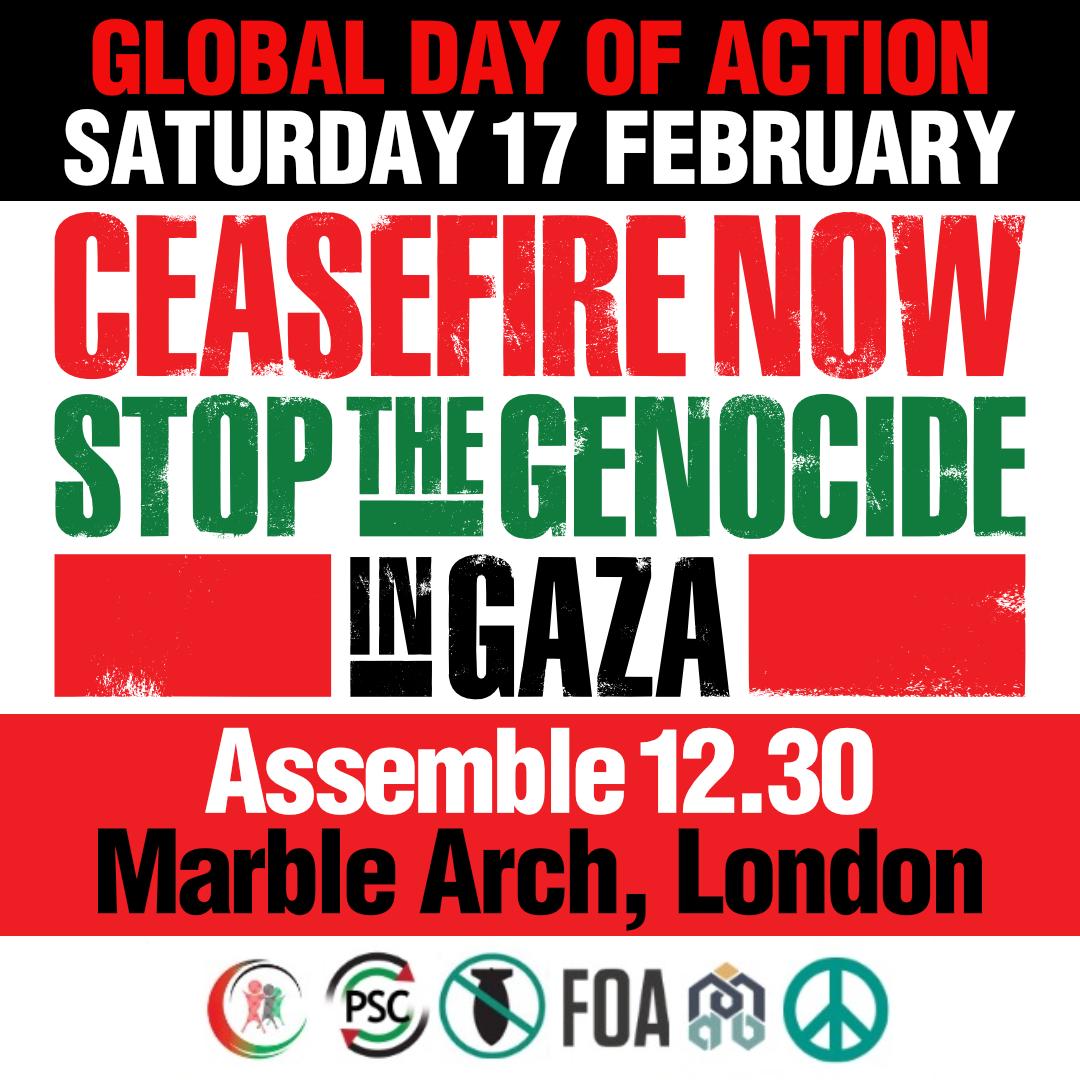

What we have done is to start to organise meetings on campus, walkouts and so on. We have got people together to go on local demonstrations in Liverpool, marching together with the banner as a contingent. We hope that will continue. I have been involved in trying to organise support for walkouts of staff and students across the Liverpool universities. Last term, on the workplace day of action on 29 November we had a film showing organised with a colleague who is an Israeli anti-Zionist. The film pre-dates the current genocide and is about life in Gaza, displaced families.

We have a newly set up Palestine Society at LJMU and one at Liverpool University. Our UCU branch set up a meeting to connect them with the campus trade unions. We talked about how students give confidence to staff, they were saying that staff can help students become more active. We discussed how to get the spirit of the protest movement into our organising in the universities.

I have spoken at demonstrations. I think it is really important to highlight the fact that I am a Jewish anti-Zionist activist. This isn’t about religion, it is about imperialism and capitalism.

I’m not a religious Jew. My immediate family were always very secular, but it was always imprinted on us that we are Jewish. All four grandparents fled from pogroms and the Holocaust.

I have always been interested in Palestine and am outraged by the idea that Israel represents all Jews. The fact that Jews around the world are standing up and saying “not in my name, this doesn’t represent me” has given me confidence.

These issues are very personal for me. My Dad who is 84 has been active politically all his life in movements like CND and the Young Socialists, he said to me for the first time that he’s scared to go out on the streets. We talked about it and he acknowledged it isn’t about the Palestine demonstrations, it is about what the narratives around Israel are doing to the safety of Jews.

This is in a context where we know there is a rising tide of anti-semitic attacks from the far right. What people like Elon Musk, Donal Trump and Suella Braverman are doing is deepening a political shift to the far right. We’ve seen Elon Musk raising the Great Replacement theory, an anti-semitic and Islamophobic conspiracy theory which claims that Jews are plotting to “replace” white people in Europe and America with Muslims. Suella Braverman has made speeches which pander to the same racist myths.

We are seeing language which hasn’t been used since the 1930s, ideas from Hitler to Moseley coming back into the mainstream narrative, with sections of the Tories moving towards fascist narratives.

I have experienced anti-semitism at first hand: someone daubed ‘dirty Jew’ across my door when I was a teacher in a secondary school.

The horrors of anti-semitism also lie deep in my family’s history. My father’s side came to England in the late 1890s from Russia and Ukraine, fleeing the pogroms. Family members ended up dispersed all over the world. My Mum’s side were from Austria, from a town we think in the Ukraine, or Poland. A place called Brody. They were pushed out by the rising tide of racism and ended up in Austria. They were reasonably well off in Austria. The family owned a shoe shop and were fairly well educated. Grandmother was an accountant. They had some family in the UK. In 1938, three sisters were granted admission to the UK working for friends of family, and escaped just before Nazi Germany took over Austria in the Anschluss. The rest of the family died of disease or starvation in Theresienstadt concentration camp.

My Mum’s dad was from Poland who moved to Belgium. He was a coal miner and an active Communist who then had to flee the country in late 1938. The government were against him and were trying to get him arrested. When he arrived in the UK the British government tried to deport him but the war started. He was put in an internment camp. When he was let out he reinvented himself as a Yiddish actor and became involved in the Austrian centre in London. We found out later he was also married in Belgium and had a family there. He was spied on by MI5, we found the files but lots of details were redacted. Then after World War Two the UK government deported him to Belgium again.

My grandad said that over 70 members of his family perished in Auschwitz. My grandparents didn’t start out as Zionists. None of their relatives today live in Israel. They were European Ashkenazi Jews, why would they want to move to the Middle East?

But in the post-World War Two world, it didn’t feel as if there were real alternatives to Zionism.

Today the situation is very different, and something positive which has come out of the growth of a mass movement of solidarity with Palestine is the emergence of a new wave of anti-Zionist Jewish activists saying clearly “not in our name”.

You can see how there is a real need to draw links between what is happening in terms of oppression wherever it raises its head, and the way that society is organised. I can’t see how anyone can separate them. There is much more interest and room today to educate people about imperialism. You can see this played out in the government’s military intervention in Yemen which it explicitly claims is all about stopping disruption to shipping in the Red Sea. Meanwhile the same government is complicit in an ongoing genocide against the Palestinians in Gaza.

As educators we have a crucial role to play in this. We need a way of engaging wider numbers of staff and students through building BDS campaigns, organising teach-ins and mobilising for walkouts and disruptive actions alongside other unions on 7 February.

At the same time we need to fight for the kind of education we create ourselves, in our communities and through our own struggles. Not the kind of benchmarking exercises imposed in academia or FE colleges, and opposed to horrible repressive systems like Prevent. Collective organisation is central to effective resistance. It all points to ways that we can change the world, to model the kind of society, practice and empathy that we are denied today.”